Culture Theft

Silvia Purdie, August 2023

Download Pdf here |

I was recently accused of cultural appropriation in my use of Te Ao Māori concepts in my work towards bicultural approaches to climate strategy. This is a significant challenge, which set me on a process of re-evaluating my motivations and foundations. It connects with key issues for the community sector as organisations seek to both honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi and begin to address environmental concerns.

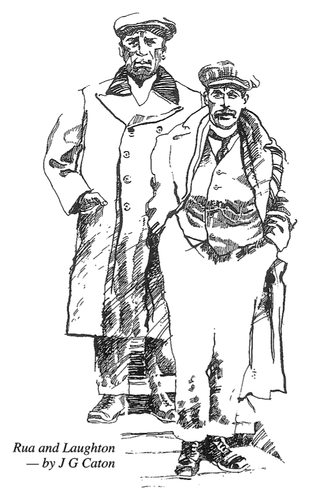

Last week I was invited to Te Whare Taonga o Taketake, the Whakatāne Museum, to view a collection of priceless treasures gathered in association with the government’s formal pardon of Rua Kēnana. Back in 1916, the government sent 57 armed police deep into the Urewera to Maungapōhatu to arrest Rua Kēnana on charges of sedition, pacifism and evading arrest. The events of that day are deeply shameful. Two men were murdered, and police ransacked every house and stole every taonga they could find. Dozens of ancestral pounamu, taiaha and feather cloaks found their way into Pākehā hands and adorned the offices of government departments. That is brutal cultural appropriation: state-sanctioned theft.

Pākehā step into bicultural space with trepidation, because frankly our track record is pretty appalling. Our history is littered with broken promises, stolen taonga and intergenerational trauma. Is it OK for Pākehā to speak Te Reo Māori or engage with Māori ways of viewing the world? This is contested space, with damaged trust and unbalanced power, and we had better be darn sure why we enter it.

I am a middle-aged middle-class white woman self-employed in sustainability. If it looks as though I am using Māori concepts to advance my own career and income, then that is a bad look. Working independently enables me to form a unique perspective, but it makes me vulnerable. Why do I put myself out there and why do I care so passionately about the bicultural journey?

While Rua Kēnana was in prison, the Presbyterian Church arrived in Maungapōhatu. Rev. John Laughton and several powerhouse women committed their lives to the Tūhoe people at huge personal sacrifice. Rua invited them to establish schools and teach the children. A partnership was formed between Perehepetīriana and Iharaira Churches. Our Pākehā missionaries became fluent in Te Reo Māori and highly respected right through the Bay of Plenty. Hoani Rōtana (as he was known by Māori) became a national advocate for Māori rights and language. He established Te Maungarongo Marae in Ōhope as a national home for the Presbyterian Church and a embodiment of Treaty partnership.

This has become my story, and the place where I stand. I cannot explain why I feel so deeply the importance of Māori language and culture to me personally. But when I sit on the step of Te Maungarongo looking through the trees at the waves it makes perfect sense. Here is the cord that binds together the things of greatest value: my faith in Jesus Christ, this beautiful land of Aotearoa, and the belonging of all of us in this place. We cannot ignore the experience of Māori people. We must form behind them in advancing their aspirations. The Treaty of Waitangi is more than a foundation for bicultural partnership; it is our home.

And so I do step forward, with trepidation, in my personal bicultural journey. I’m working to become more fluent in Te Reo Māori. I am committed to helping the church, especially the Presbyterian Church, to know, grieve and celebrate our history, and to honour Māori in our shared life. As we grapple with climate change I long to see us all growing in the knowledge of where we come from, where we stand, and how we can work together.

Reference: ‘Te Hinota Maori: The Maori Synod, Maori Spirituality and Ministry’, Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand, 1992. https://pcanzarchives.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/117388

Sketch by J.G. Caton from a photo of Rua Kenana and John Laughton at Maungapōhatu.

Last week I was invited to Te Whare Taonga o Taketake, the Whakatāne Museum, to view a collection of priceless treasures gathered in association with the government’s formal pardon of Rua Kēnana. Back in 1916, the government sent 57 armed police deep into the Urewera to Maungapōhatu to arrest Rua Kēnana on charges of sedition, pacifism and evading arrest. The events of that day are deeply shameful. Two men were murdered, and police ransacked every house and stole every taonga they could find. Dozens of ancestral pounamu, taiaha and feather cloaks found their way into Pākehā hands and adorned the offices of government departments. That is brutal cultural appropriation: state-sanctioned theft.

Pākehā step into bicultural space with trepidation, because frankly our track record is pretty appalling. Our history is littered with broken promises, stolen taonga and intergenerational trauma. Is it OK for Pākehā to speak Te Reo Māori or engage with Māori ways of viewing the world? This is contested space, with damaged trust and unbalanced power, and we had better be darn sure why we enter it.

I am a middle-aged middle-class white woman self-employed in sustainability. If it looks as though I am using Māori concepts to advance my own career and income, then that is a bad look. Working independently enables me to form a unique perspective, but it makes me vulnerable. Why do I put myself out there and why do I care so passionately about the bicultural journey?

While Rua Kēnana was in prison, the Presbyterian Church arrived in Maungapōhatu. Rev. John Laughton and several powerhouse women committed their lives to the Tūhoe people at huge personal sacrifice. Rua invited them to establish schools and teach the children. A partnership was formed between Perehepetīriana and Iharaira Churches. Our Pākehā missionaries became fluent in Te Reo Māori and highly respected right through the Bay of Plenty. Hoani Rōtana (as he was known by Māori) became a national advocate for Māori rights and language. He established Te Maungarongo Marae in Ōhope as a national home for the Presbyterian Church and a embodiment of Treaty partnership.

This has become my story, and the place where I stand. I cannot explain why I feel so deeply the importance of Māori language and culture to me personally. But when I sit on the step of Te Maungarongo looking through the trees at the waves it makes perfect sense. Here is the cord that binds together the things of greatest value: my faith in Jesus Christ, this beautiful land of Aotearoa, and the belonging of all of us in this place. We cannot ignore the experience of Māori people. We must form behind them in advancing their aspirations. The Treaty of Waitangi is more than a foundation for bicultural partnership; it is our home.

And so I do step forward, with trepidation, in my personal bicultural journey. I’m working to become more fluent in Te Reo Māori. I am committed to helping the church, especially the Presbyterian Church, to know, grieve and celebrate our history, and to honour Māori in our shared life. As we grapple with climate change I long to see us all growing in the knowledge of where we come from, where we stand, and how we can work together.

Reference: ‘Te Hinota Maori: The Maori Synod, Maori Spirituality and Ministry’, Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand, 1992. https://pcanzarchives.recollect.co.nz/nodes/view/117388

Sketch by J.G. Caton from a photo of Rua Kenana and John Laughton at Maungapōhatu.